By all accounts Bruce McLaren was an amazing race car driver, founder and boss of his own auto company, and family man who accomplished more by the time he died at the age of 32 than most people who live two or three times as long.

Prophetically, McLaren once said, “I feel that life should be measured in achievement, not in years alone.”

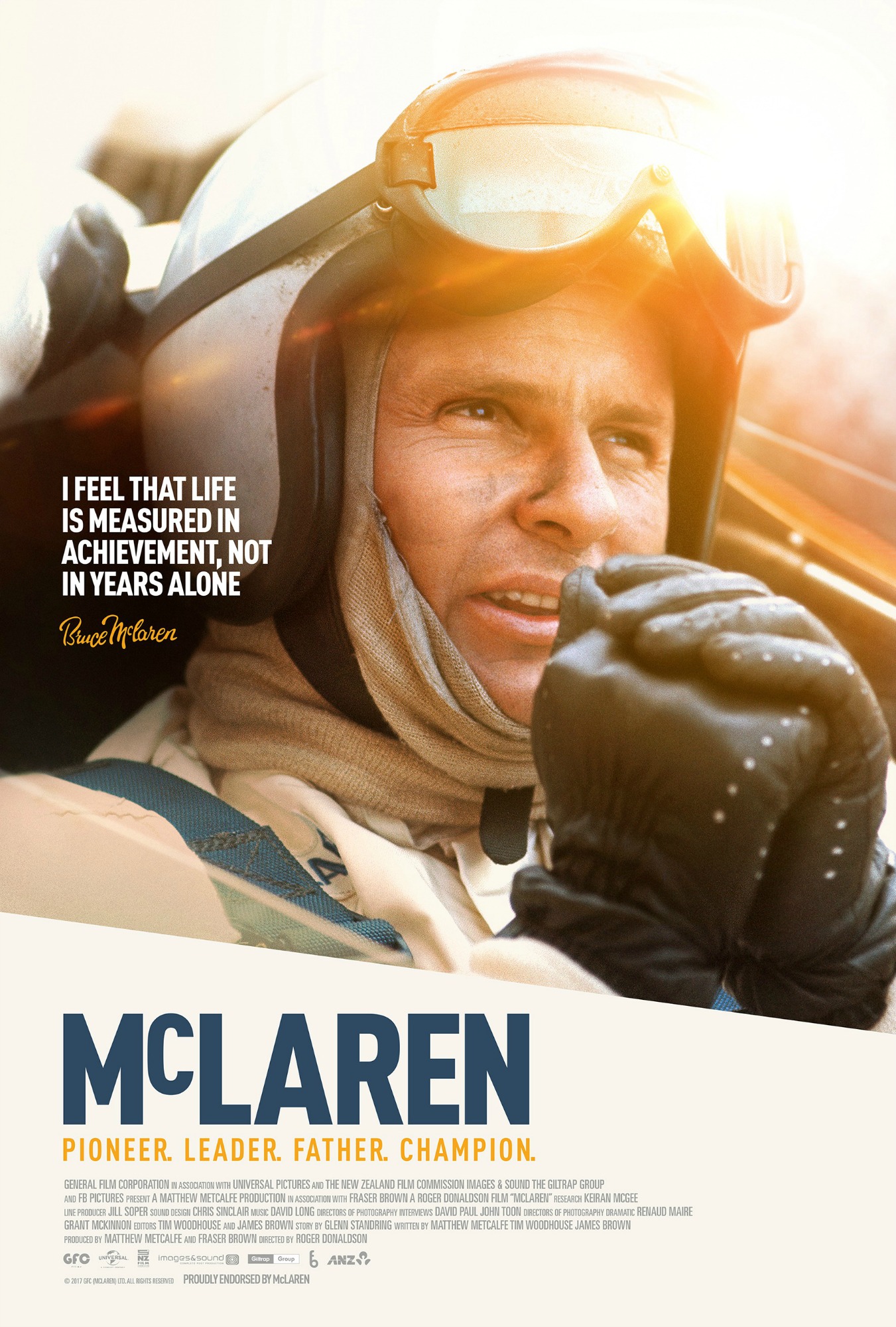

The story of the New Zealander who impacted motor sports forever as a driver and owner is shared in a way that will have broad appeal and appreciation by any viewer in the new Gunpowder & Sky documentary, “McLaren,” from Australian-born New Zealand immigrant Roger Donaldson.

Among his many credits, Donaldson directed the 2005 dramatization “The World’s Fastest Indian,” about another New Zealander racer who set the land speed record on a motorcycle.

In a screening Saturday (June 24, 2017) at the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, Donaldson said it was important for him to make this movie to showcase the person for whom the name was derived for the familiar McLaren brand of race cars over the last half-century and the now-familiar high-end cars launched for the consumer market in 2011.

Recounted chronologically from his birth in 1937 with a pleasantly surprising amount of archival footage from the 1950s and 1960s and some dramatic re-creations sprinkled harmlessly and nearly seamlessly throughout, the 92-minute film begins by showing McLaren’s childhood physical challenge with one leg significantly shorter than the other, which kept him bedridden for nearly two years and barred from playing sports by his doctors.

But he managed to turn his work experience at his father’s auto shop in Auckland into a knowledge of engineering that exceeded his peers as he became the youngest Formula One driver to win a Formula 1 Grand Prix race at age 22, then the Le Mans, and followed remarkably soon thereafter by designing his own cars that beat the likes of Ferrari on the world’s biggest stage.

Many of these individuals share poignant memories of the fateful day on a test drive in England in 1970 in preparation for his first attempt at the Indy 500 when he crashed and his body was horribly broken upon impact.

Patty recalls in the film that he was tired from recent travels, going on little rest and probably should have left the driving of his cars to others by that point in his career since he was so busy running the company, but he loved driving and was anxious to take on the challenge of the Indy 500.

His legacy was assured when McLaren cars won the Indy 500 in 1972 (Mark Donohue) and again in 1974 and 1976 (Johnny Rutherford), while also winning the Formula 1 championship those same years with drivers Emerson Fittipaldi and James Hunt, and nine more since then, the most recent driven by Lewis Hamilton in 2008.

— By Scott Hettrick