The boy who was playing young Opie Taylor on the iconic “The Andy Griffith Show” when The Beatles took the world by storm in the mid-1960s has grown up to direct a notable cinematic chronicle of their short-lived days on the road from 1964-1966.

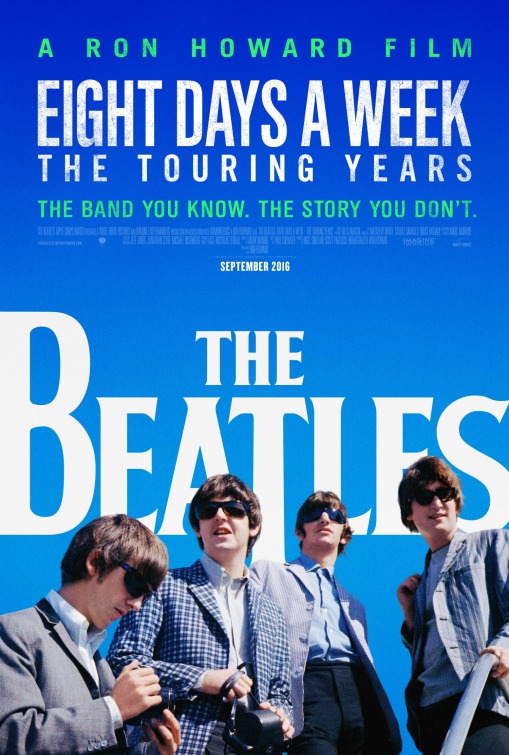

Perhaps not wanting to wait until when he’s 64, the 62 year-old Ron Howard’s 95-minute documentary, “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years,” premieres primarily on Internet entertainment site Hulu.com today, Saturday, Sept. 17, 2016. It’s also in a few select movie theaters around the country but the Hulu HiDef presentation is excellent. (As a side note, the closed captioning option on the Hulu version is of some benefit during some spoken dialogue that is difficult to understand due primarily to thick English accents and poor quality initial recordings, especially at the beginning of the film.)

Perhaps not wanting to wait until when he’s 64, the 62 year-old Ron Howard’s 95-minute documentary, “The Beatles: Eight Days a Week — The Touring Years,” premieres primarily on Internet entertainment site Hulu.com today, Saturday, Sept. 17, 2016. It’s also in a few select movie theaters around the country but the Hulu HiDef presentation is excellent. (As a side note, the closed captioning option on the Hulu version is of some benefit during some spoken dialogue that is difficult to understand due primarily to thick English accents and poor quality initial recordings, especially at the beginning of the film.)

Although not overtly telling the complete story of The Beatles, the new film that covers specifically those years that The Beatles were on tour can’t help but provide an overview of the story of the Liverpool lads. Few remember that The Beatles only existed as a comet-like band for a mere seven years and played their farewell concert on the roof of their Apple offices and recording studio in London on January 1969, less than five years after their first spectacular appearance in America in February 1964.

After a brief set-up of the band’s formation and release of the first album in 1962, and building popularity in Europe where a line for concert tickets in 1963 extended for a mile, the next 70-minutes focuses on the heady years of the Mop Tops in 1964 – 1965, with some fresh performance and behind-the-scenes footage and an impressive amount in color or very vivid black-and-white.

- The Vietnam War was escalating.

- The Cold War and the Cuban missile crisis were still causing great unease.

- The NASA space program in full swing to get man on the moon by 1969.

- Racial and civil rights issues were sparking protests, riots, and political unrest.

And the simultaneous seismic events in pop culture were nearly as large:

- The controversial biting political movie satire about the nuclear bomb, “Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” hit theaters just days before The Beatles landed in New York in February 1964.

Muhammad Ali was a huge story and would shock the world by winning the world heavyweight championship against Sonny Liston days after The Beatles arrived in America.

Muhammad Ali was a huge story and would shock the world by winning the world heavyweight championship against Sonny Liston days after The Beatles arrived in America.- The first Mustang cars were sold by Ford two months later in April 1964.

Into this environment came The Beatles, with George only 20 years-old, Paul 21, and John and Ringo each 23. They were led by a manager who was all of 27 years-old, Brian Epstein.

It seems incredible that in just the ten days these five British youngsters were in America for the first time, they eclipsed the headlines of all those other news-makers, and would continue to do so for the next several years.

Howard brings this down to a more personal experience level with comments from celebrities like Sigourney Weaver and Whoopi Goldberg, the latter of whom becomes emotional when recalling the effort her mother must have gone through to get two tickets to The Beatles concert for her. She also notes that it was The Beatles who inspired her to have the courage to become her own person.

Another black woman recalls attending The Beatles concert at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida in September 1964, the first time she had experienced being at an event where she was allowed to mix (integrate) with white people, and the impact that had on her — officials had planned to segregate the crowd by race but The Beatles decided as a group not to allow it at any of their concerts.

Newly-recorded interviews with surviving Beatles Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr are sprinkled sparingly throughout, intermingled with archival interviews with them and John Lennon and George Harrison.

On the initial tours in the U.S, which resumed in August 1964 after an overseas tour in countries including Australia and New Zealand, concert attendance was considered large at about 8,000 fans.

Only a year later, in what is described as probably the first national stadium concert tour, audiences would swell to 20,000, 25,000, 35,000, and eventually 56,000 at Shea Stadium in New York in August 1965.

As the movie covers each step on The Beatles tours, mostly chronologically, there is a subliminal impact of wonder as the dates and projects are noted:

- A Hard Day’s Night movie and album were recorded and released in July 1964, just a few months after coming to America the first time, a month before returning to America, and in the midst of The Beatles first world tour.

- The Beatles music producer George Martin and manager Brian Epstein agreed that they needed to put out a new Beatles single (record) every month and an album every three months (apparently including the many compilations and variations that were released during this time).

- Two more albums of all new material were released in 1965, Help! (the title song by John Lennon an honest expression of the growing stress he was feeling), and Rubber Soul in December 1965, featuring a completely new style and sound that was initially rejected by many.

- A second movie to accompany the album Help! was filmed in the Bahamas (with the Beatles “slightly stoned” throughout, according to Paul McCartney in a current interview for the film), again amidst an ongoing global concert tour that included stops in Paris and Spain.

Ringo reflects that part of the reason for the manic concert tour schedule was that “we (The Beatles) didn’t make any money on the records” but they did make money on the concerts.

But even the financial incentive was wearing so thin by this relentless schedule that all four of them had grown weary of the grind by the end of 1965. Also, the screaming fans were so loud and the band’s small amplifiers so low-tech that the music was drowned out for everyone, including the band members. At Shea Stadium the audio of the instruments was fed through the public address system, sounding no better than thousands of transistor radios. Ringo recalls that they couldn’t hear themselves playing — “I had to watch John (playing his guitar) to see where we were in the song,” he says.

Things got significantly worse in 1966, for which Howard devotes about 20-minutes near the end of the film. It is noted that George was discovering Indian music, band members were wanting to spend more time on their own and with families and expend less time and energy with Beatles activities and events. Mostly, they wanted to spend more time in the studio and with musical experimentation. (The Revolver album was released in August 1966).

Meanwhile, concerts in 1966 were getting more dangerous; a riot in Cleveland, a bomb scare in Memphis, pouring rain at an outdoor venue in St. Louis.

There was a growing anti-Beatles sentiment, including one that sprung from a miscommunication in the Philippines when The Beatles were said to have snubbed an appointment with First Lady Imelda Marcos. Then there was the flap in the summer of 1966 over John Lennon’s comment on vacation between concert tours that The Beatles were bigger than Jesus.

McCartney recalls that Harrison was the first and most vocal with the idea of ending the concerts, but the others soon joined in his sentiment.

And then it was over; no more Beatles concerts after a whirlwind 2 1/2 years.

Howard ends the film with a text postscript noting that The Beatles began working on their next album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, just three months later and would produce five albums over the next four years, culminating with the rooftop concert that ends this film (except for a fun piece of audio recorded in the studio as a promotional piece where all four Beatles thank their fans and wish everyone a Happy Christmas, which plays over the last half of the final credits).

The movie is appropriately dedicated to George Martin, who died earlier this year.

There are more comprehensive Beatles documentaries, and some that are more powerful, but Howard’s “The Beatles: Eight Days A Week — The Touring Years” offers a refreshing slightly new angle on a specific aspect of this amazing moment in time for these young men, and for many of the rest of us as well.

— By Scott Hettrick