Garth Brooks says it could quite possibly be the greatest song in music history and was pivotal in launching his career.

Pete Seeger said he couldn’t get the song out of his head.

Buddy Holly took that fateful plane trip because he had some laundry he wanted to get cleaned.

Don McLean says those famous lyrics don’t refer to Elvis or mean anything else you may think:

Oh and while the King was looking down

The jester stole his thorny crown

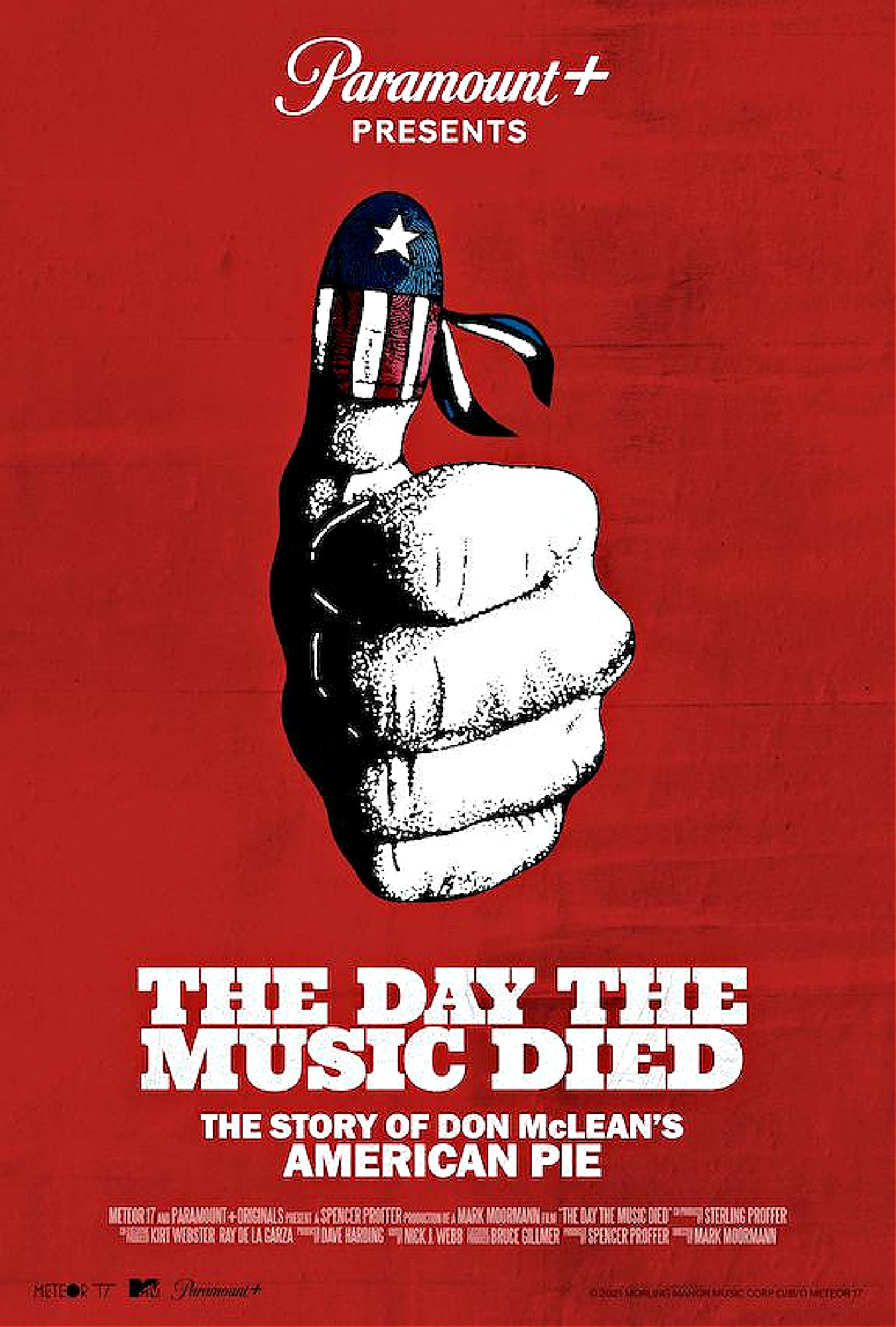

On the 50th anniversary of the iconic eight-and-a-half-minute chart-topping single American Pie (actually, the 51st anniversary since the song was released in 1971), a new 95-minute documentary streaming on Paramount+ (July 19), The Day the Music Died: The Story of Don McLean’s “American Pie,” provides many such insights and fascinating bits of trivia.

(review continues below the following image… )

The first 25-minutes of the film recounts the details of the night in 1959 when a small airplane crashed in a remote farm field in Clear Lake, Iowa, killing three of the biggest rock and roll stars of the era, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. Richardson (The Big Bopper).

This is related mostly by local Clear Lake farmer Jeffrey Nicholas, whose family still owns the field where the plane crashed, but he didn’t even realize that until about 20 years later.

As a refresher for the story, facing another heater-less bus ride in severe cold temperatures to their gig in Moorhead, Minnesota that was already causing frost bite for some musicians of the Winter Dance Tour, Buddy Holly asked the manager of the Surf ballroom to find a plane he could charter for he and his band members, Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup. A 21 year-old pilot, Roger Peterson could take them from a small airport in nearby Mason City, Iowa, shortly after midnight. Jennings gave up his seat to The Big Bopper, who was suffering from the flu. Valens asked Allsup to flip a coin for his seat. Valens won the toss.

The late Jerry Dwyer, who owned the ill-fated aircraft and managed the airport, is shown in what must be an interview from at least a decade ago (though this is not indicated), saying he put all three performers in the airplane that night and saw the lights descending in the distance, but was told it was an optical illusion. In fact, pilot Peterson is believed to have become quickly disoriented (but this has never been verified).

It was hours after the plane crash before anyone even knew anything had happened to the singers, and it was the next day before the downed plane and all four bodies were found (first by Dwyer) just a few miles from where it took off, having nose-dived straight into the ground.

(review continues below the following video trailer…)

As most will remember, it began as the song describes in the second chorus when a 13 year-old McLean was delivering newspapers on his bicycle in New Rochelle, New York and saw the news on that fateful day in the winter of 1959:

But February made me shiver

With every paper I’d deliver

Bad news on the doorstep

I couldn’t take one more step

McLean, now 76, says that after he read the news, he bought the quickly-released tribute album The Buddy Holly Story and was moved and touched by all the hit songs and wanted to become a performer himself. But his father discouraged this “silliness” as taking time away from his school studies, where he was not making high marks. A couple years later, when McLean was a freshman at a prep school, his father came home and saw a particularly bad report card and yelled at McLean. Several hours later, his father came into his son’s bedroom crying, clutching his chest, and saying: “God help me.” An ambulance came and a few hours later his father was pronounced dead of a heart attack.

McLean turned to his music, started writing songs and performing locally on a regular basis, eventually quitting school at about age 17 or 18.

With only five-minutes of this story segment having elapsed, the viewer is abruptly introduced to Valens’ sister Connie, talking about her long-departed brother. She is clearly grateful for the attention his song brought to the brother she lost when he was only 17. “It was another little bit of healing for our family,” she says. She’s standing at a recent classic car show in Clear Lake, Iowa, and she will return several times during the next hour of the movie, including for the filming of her recent presentation to McLean with a special gift.

Where other documentaries might have let that initial half-hour be the set-up for the story of the song and McLean (even perhaps lengthier than needed), and not go back to it again, director Mark Moormann chose to keep coming back to the story of the crash, the family of the people involved, and even showcase the Surf Ballroom, all of which begins to feel more like a promotion for the community of Clear Lake, Iowa, since most of the comments continue to come from this farmer Jeffrey Nicholas. He happens to also be president of the nonprofit North Iowa Cultural Center and Museum, which operates the Surf Ballroom and who has created a small memorial for the fallen victims on his property, which is accessible to visitors.

We also keep going back to Garth Brooks gushing in a very genuine and impressive way about the impact the song had and still has on him, to the point that Brooks invited McLean to sing it with him during a massive Brooks concert in Central Park in 1997.

But these aren’t the only discordantly-arranged elements — suddenly appears a man giving history tours in Philadelphia dressed in a period costume. It turns out we’re seeing and listening to him because he claims to have seen McLean’s first live performance of American Pie at St. Joseph’s University. OK. Later we’re back to Philadelphia to see sculptor Zenos Frudakis who incorporated a sculpture of McLean as the poet representation in his Freedom piece.

And just as abruptly we keep returning to short but fascinating little snippets about McLean, many out of chronological order, including being told that despite him previously saying that he quit school, that he graduated school in 1968 (presumably Iona College, based on a brief video image of the school logo), and that he suddenly had a three-record deal.

And McLean explains that he introduced himself as a young artist to legendary singer Pete Seeger, who soon added McLean to his performing team, a pretty impressive achievement and connection. That led to McLean meeting the Everly Brothers in 1969, which is where Phil Everly told McLean that he was great friends with Buddy Holly and that Holly took that plane that night because he had dirty clothes and wanted to get to the next town quicker in order to do his laundry.

That meeting and conversation came a decade after the fateful night.

For ten years we’ve been on our own…

This story about Holly and his laundry is apparently what kindled McLean’s desire to revisit the impact the news about Holly’s death had on him, and that along with the turbulent times of the late 1960s, McLean felt America needed a big song. Thus came American Pie, the name being a condensation of being as American as apple pie, and pulling bits of lyrics from Seeger’s Bye Bye My Roseanna, and “This’ll be the day” from a similar John Wayne line in The Searchers.

Round this all out with McLean explaining what most of the somewhat vague and puzzling lyrics mean – but not all — and you have the story of McLean’s American Pie and a lot more (and maybe some less) than you expected.

— By Scott Hettrick