Thirty years ago Charlton Heston told me in a phone interview for The Kansas City Star that he lamented the fact that home video was resulting in fewer people seeing movies in theaters like his epic “Ben-Hur” of 30 years prior.

Thirteen years later Heston invited me to his home in 2002 to discuss an animated home video version of “Ben-Hur” being produced by his son Fraser, and we again noted the unfortunate inability for audiences to see his 1959 classic the way it was intended on the big screen.

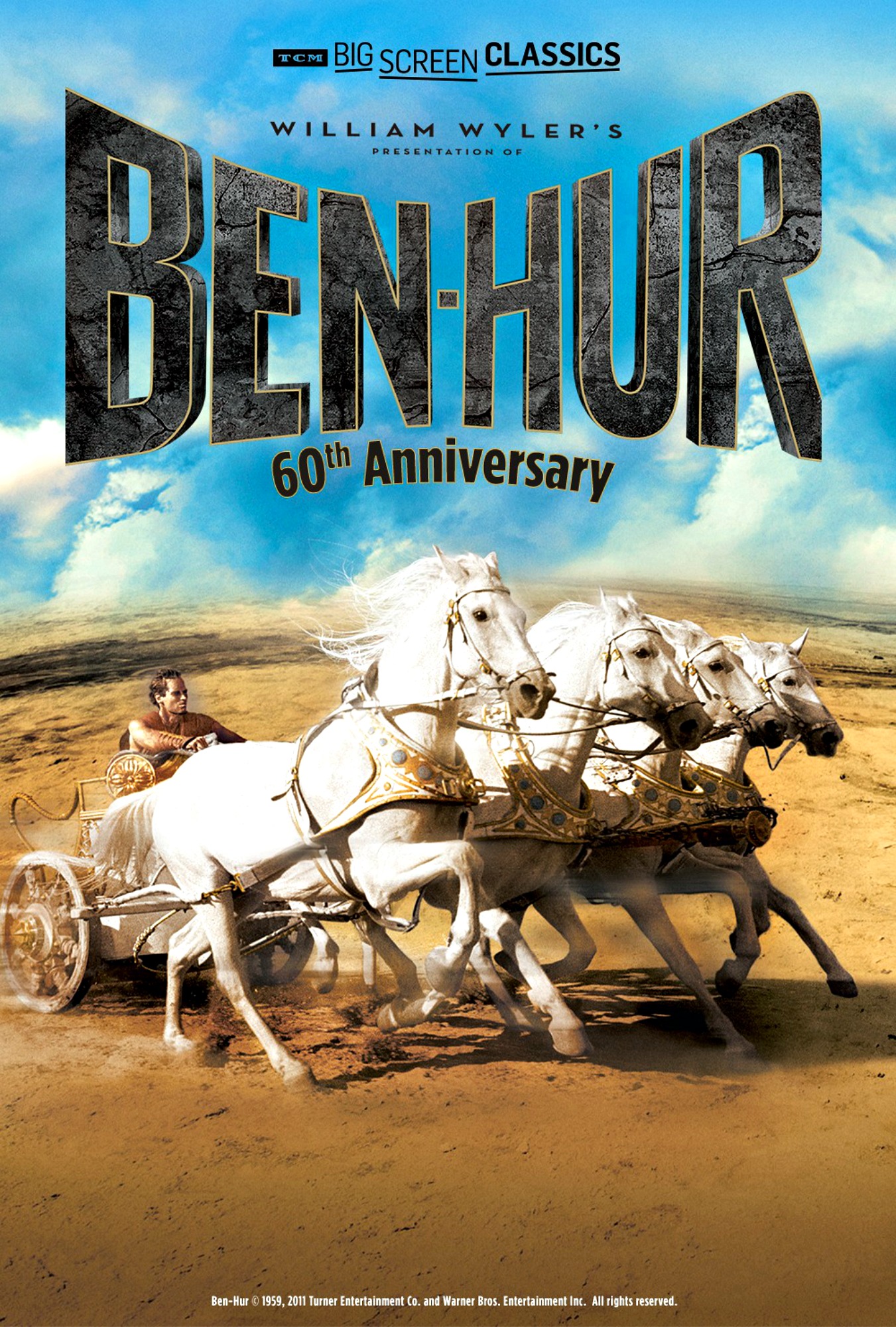

Now, on its 60th anniversary, that nearly four-hour monumental film has returned to 600 theaters nationwide through Fathom Events for four showings in two days — today (April 14) and a matinee and early evening showing on Wednesday April 17. And it is still worth the price of admission, maybe even more-so than ever before because the sound is superior and the digital image is immaculate. The famous and stunning 10-minute chariot race never looked more impressive.

The most expensive movie ever produced at the time ($130 mil. in today’s dollars), which had a $1 million frame-by-frame restoration for Blu-ray in 2011, is presented digitally complete with the six-minute pre-film “walk-in music” overture and 15-minute intermission (following the first 2-hours and 24-minutes), and in its original widescreen 65mm format (it was originally shot in MGM Camera 65 format with Ultra Panavision camera lenses, which is nearly three times wide as it is tall – a whopping 2.76:1 aspect ratio – and is being billed by Fathom as Ultra 65).

“Ben-Hur” is the tale of Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish Prince and the leader of Jerusalem during the Biblical times of Jesus Christ (the movie, like the Lew Wallace book it is based on, is subtitled: A Tale of the Christ). Heston is in command of this Oscar-winning performance that has him on screen in almost every scene (it was just three years after he was Moses in “The Ten Commandments”).

As the Romans are trying to get the Jews of Judea to show more reverence to the emperor, Judah’s former childhood friend Messala (Stephen Boyd) becomes a power-hungry Tribune and suddenly decides to make an example of Judah to send a message to the other non-conforming Jews. He sends Judah’s sister and mother to prison for four years (they eventually wind up in a leper colony) and sentences Judah to slave labor rowing a ship for three years. Judah winds up saving the life of the ship’s merciless captain during a battle, and the captain shows his gratitude by adopting Judah as his son and training him to drive his chariots in competition. Judah eventually heads back to Judea to seek revenge against Messala, but along the way he meets a sheik owner of Arabian horses (Hugh Griffith, Best Supporting Actor) who asks Judah to drive them in a race at Circus Maximus in Rome against Messala. Perfect!

Of course there’s a woman of romantic interest who comes in and out of Judah’s life during the film – Esther is played well by Haya Harareet.

Several times in Judah’s adult life, his path fleetingly crosses that of Jesus of Nazareth, and each time he is awed by the generosity and aura of the man. After the 25-minute chariot race segment that opens up the 75-minute second half of the film – the actual race lasts a riveting 10-minutes — this devout Jewish leader brings his mother and sister to see Jesus hoping that he can cure their leprosy but when he arrives he finds Jesus dragging his cross and being crucified. Nonetheless, they are cured anyway during a rain that follows.

As is often the case in Fathom presentations, it is being presented in partnership with cable network Turner Classic Movies under the banner of the TCM Big Screen Classics Series. (“Gone with the Wind” recently wrapped a record four-day presentation for Fathom with $2.2 mil., eclipsing the record set in January by “The Wizard of Oz,” which combined with “Dirty Dancing” have collected a combined $5.5 mil.) TCM primetime host Ben Mankiewicz provides his familiar introductory and post–show remarks (four-minutes at the beginning here), offering context and notable background information about the film. As was the case in this era, the closing credits amount to little more than a card saying The End, followed by another couple of minutes of Mankiewicz comments.

Also reflective of the 1950s, “Ben-Hur” has a slower style of pacing than modern films, and like “The Ten Commandments,” can feel somewhat earnest and melodramatic at times, with the Oscar-winning score occasionally overwrought, but this presentation offers a rare and pleasing opportunity to experience the big-screen spectacle of a by-gone age of movie-going.

— By Scott Hettrick